That indecent noise- part 2

a child of hip hop Golden Era reflects on ideology and cosmology and imagines what hip hop could have been

Once again, the title of this freestyle spit comes from a quote by Black Thought

The song is long liveth -

“feeling the deeper void listening to

that indecent noise

people used to tell me

boy, your brain gon be destroyed”

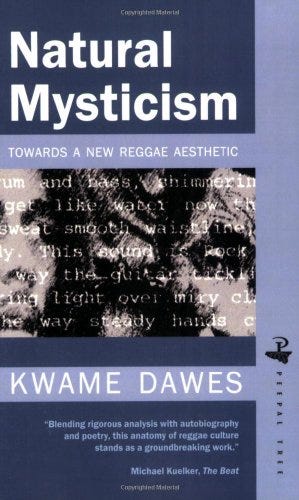

I can’t overstate how much I’m digging Natural Mysticism by Kwame Dawes. I think it’s because we both are intellectual middle class Afrikans who grew up in the midst of a powerful cultural moment. For him it was reggae of the 1960s and 70s. For me it was the Golden Age of hip hop in the 1990s. That book is his attempt to wrestle with how and why reggae is a cultural force that transcends just music making. The book combines autobiography with cultural analysis.

It’s timely that I am reading this while in the second half of my MFA study in nonfiction. There are some other Afrikans, including of course the homie Zia who is in nonfiction with me (DC in the house!). But we are too’s and few’s. It’s not even every workshop that I have another Black person with me. Only been one time out of three.

More than that, I feel more and more that my creativity is carrying something that my peers and classmates don’t have. It’s imprecise to just call it “being Black.” I’ve performed as an MC formally and informally much longer than I’ve been writing for publication. I’m a voracious reader, yet I’ve still spent more time listening to music from hip hop culture than I have reading. Over the course of my life, many more people have heard my raps, my freestyles, my spoken word, my performances,my MC’ing than have read my written words, though I will celebrate the day in the future when that is no longer true. It probably hasn’t been true in the last 4 years.

My younger brother Lee was a rapper by the name of Bishop. In addition to drumming in the Renaissance High School marching band, he rapped at high school parties, rapped on the radio once in a while. It was his goal and his dream to move to New York and become a rapper. We would listen to Mobb Deep in my father’s jeep and he’d tell me his plans of not going to college. I’d share my raps with him and he’d always say they were “just aight.” My first rap teacher, Lee is the subject of my poetry book of my modern era, Lee Young Lee. This book wrestles with the fallout in my heart and in our family after Lee’s suicide at age 16.

Kwame Dawes points out 4 aspects of the reggae aesthetic. First its ideology, which includes mythology, cosmology and historical concerns. Second, are the way that it uses language politically and formally. Third, the particular way that reggae music addresses its themes. And finally, the form, the internal structure of the music and the cultural creations such as dance that bloomed around it.

Is it asking too much for me to have spelled out each of these four areas and how they relate to growing up in Detroit in the 90s, becoming a poet-MC and entering manhood in the early twentieth century?

Yes, it’s too much for a single freestyle to break all of this down. But I’ll look at each of them a little bit.

First- ideology and cosmology.

Hip hop is based upon the power of nommo, the spoken word as a force of creation. It contains some description, but a lot of its power is in its ability to promote a new future. To assert that “we gon make it” or “we gon be all right.” It’s not the same as “fake it to you make it.” It’s a metaphysical ancestral way of speaking truths into existence. It’s also not just description, it’s not just telling how bad it is. Success is claimed, is embodied, is declared as a way of helping folks that aren’t given any pathways in education or employment the energy to change their surroundings.

While hip hop is stereotyped as being egocentric and “I” driven, there are strong threads that are projections of “we.” As in poetry, the persona of the “I” is offered to the listening public for the folks to identify with. Hip hop puts “the streets” at its center. The MC places their lives, their struggles, their success, and their powers in the context of the lives of Black and brown people oppressed and excluded .

Jay Z asks, “How you gon’ rate music that thugs with nothin relate to it? I helped them see their way through it. Not you. Can’t step in my pants. Can’t walk in my shoes.”

Lastly (for now), hip hop asserts its own morality. The morality is that of survival. It’s been a rejection of “respectability politics” before that phrase was popularized. Allen Iverson brought hip hop style to basketball. Jodeci brought hip hop style to R & B. Hip hop asserts that we come from a culture that creates its own rules by the necessities we live for survival. Black entertainers used to be expected to be clean cut, to fit within the morality of the dominant system, the professed morality of the businessmen who own the microphones, the clubs, the stadiums, the media outlets. We might say that hip hop seeks success on its own terms. It’s a rebellion against generations whose lives were overdetermined by those who paid our bills, those who offered employment, those who worked us half to death and made our survival something that we could never ever take for granted.

As Jay Dee says “Fuck you. Pay me.”

This mix of hip hop cultural ideologies does have (did?, we ask, a tear dripping down our aging faces) a powerful potential for revolutionary consciousness. To use promotion of vocal energies to build a collective future that is independent of the dominant narrative and is willing to do what it takes to make the change happen. My patna Shamako Noble philosophizes about why this consciousness was not realized as it could have been. I think the phrase “independent of the dominant narrative” is key. There was a moment when underground hip hop was vying for control of hip hop culture. That moment slipped away. I’m excited to see how Shamako puts it out and lays it down.

Unfortunately too much hip hop is about the emulation of the ways of financial success that America waves in front of its citizens as the American Dream. It was easy for rappers who received commercial success to become spokesmen for the American Dream while claiming to be speakers for an oppressed culture instead of leaders of a culture that was truly charting pathways of independence and dare I say, sovereignty. Too many of the visions of success involve creating the capacity to leave the ghetto, not the ability to transform the ghetto. Too many of the rap visions of soldiering involve taking on and taking down the people who look most like us, not taking on the gentrifiers and forces that seek to control the ghetto.

Growing up in Detroit, a child of the middle class with family members that strutted and slid in and around poverty. I was attracted to hip hop as a way of speaking to “my people” in ways that schooling didn’t prepare me to do. My Granny would say to us often– maybe just to me???-- “Don’t be an educated fool.” I did find, I must confess, that I could not live within the boxes of masculinity that hip hop proscribed. I turned to poetry to find vulnerability, mourning and what felt to me to be emotionally rounded expressions. It’s no coincidence that as I’m thinking about my positioning with regards to the world of literature that hip hop is calling me to look more closely. To pull up for a sec and let the beat play as my pen game grows and I “chant down Babylon” inspired by the writings of OG Kwame Dawes.