Recap of Autumn 2024- part two

Here are some books I've picked up along my journey. Here is a creative journey in school in America, on earth, underneath the cosmos.

Happy New Year, everyone!

In a week, I’ll be starting a new semester.

For the calendar flip, essayist and cultural critic Harmony Holiday shared a James Baldwin quote which was nourishing, activating, and challenging.

“When you’re writing, you’re trying to find out something that you don’t know. The whole language of writing for me is finding out what you don’t want to know, what you don’t want to find out. But something forces you to anyway.”

Nourishing because this affirms what they’re teaching in my MFA program at Pacific University on how to write into the cracks of your own understanding. But more than just affirming what others are telling me, it’s reassuring that writing is hard-ass work. It’s an emotional labor. One amongst others in my life as a father with chronic illness. It’s a struggle to feel like I’m writing what needs to be written. This quote reflects my experience in the MFA program, which has raised the bar for my own writing. It’s not just calling me to evaluate how the words sound, but also how they move me as a reader, editor, revisor.

It’s Activating to read this as I head into another semester. It’s been a whirlwind parenting my son into his first semester of middle school. As soon as the semester was over, I couldn’t even look at my own writings, much less revise them. I needed December to be a month of rest, a month where I work with my partner (and my ex as much as possible) to evaluate and transform our co-parenting processes. I’m glad I can write some Stacks in this in-between time. The time to get back to Collapse is approaching. I’m making a commitment to you to sharing a little bit more on my Stack during the semester. (Some will be paid; some will be open). I’m coming up with a plan.

Challenging. Like a reminder from an elder that knocks you upside the head a little bit. The gap between writing what you (think you) know and writing into the unknown and what you haven’t even thought yet can be intimidating. I came into nonfiction in many ways to try to put words to my intuitions and the energies I observe around me. But I’m trying to move past mere reporting and push the needle further into my own heart.

I’ll admit that part of why I like the Substack writing is because here I don’t put as much pressure on my self to dig deep into my cardiac tissue. I got a call from my cardiologist’s office this afternoon with test results. I let it go to voice mail. It said the word “recommendations.” I am steeling myself to return the call. But this year I’ll share a little bit more of what’s in process especially for subscribers.

When I don’t feel like writing “for school” I can write to the Stack. It feels a little more like play to me. Yes, it may be messed up that a chunk of my own writing now feels like it’s writing “for school.” We’ll cross that bridge soon enough. Fingers crossed, it will be this June. What haunts me now— I see Baldwin knocking my head again— if I’m holding back now, what makes me think I’ll stop holding back when I’m writing after graduation? Am I holding back or do I just not know how to say what I want to say?

Baldwin’s quote above makes me think of Esu, the crossroads, messenger god, in the Yoruba tradition. This year, as I wonder if I’ll get back on the transplant list (my cardiologist’s approval is an essential ingredient to that recipe); as I work my narrow ass off to strengthen my heart and align my chi; as I weather the downs and ups and feel like some seasons my health takes three steps back; as I reflect on the last 15 years of hemodialysis I appreciate being part of a tradition that views the trickster, the playfully divine holder of the unknown, as the gateway to Orisha, to the realm of spirit, to embodying our ori/destiny ever more fully.

Write what I don’t know? Fuck, I’m living it and it’s tiring.

This morning, my partner reminded me of a key happening this December. My son was called the “n word” by a player on his opposing hockey team. He ended up fighting, and beating three players on that team. He and another player were kicked out the game. He sat on a bench to watch the game and was then called the “n word” again by a player’s mother. This semester he has asked me to write a story in which a Black person beats up a white person. I’m very aware that I haven’t written that story yet. But here he goes, living it in the flesh since I was taking so long to put it onto paper.

I’m sitting with the tension of seeing myself as being in combat, a long multi-generational affair, with this hegemonic system of products, norms, and thought while taking out loans to be enrolled in a school that continues and advances the culture of Western letters.

I’m from Detroit. When I grew up it was an undeniably Black city. Now it is a majority Black population but there are major forces here trying to make it into something else, advertising to new comers that they can turn it into something else, something better. This tension is the premise of my book-in-progress Collapse; it’s the struggle my son faces on the ice and in the school room; it’s what I feel when I’m in workshop class in the American Pacific Northwest.

Hope you enjoy these words on the journey.

If you want to support a chronically ill father who is also an essaysist, then consider becoming a paid subscriber. Consider adding your pennies or dollars to the Calabash.

Here is some reporting:

Every semester we have to read 20 books as part of the MFA curriculum. We talk about “reading like a writer.” I’m glad our program allows us, forces us, to create our own book lists.

I’m sharing this, and all the other semester end Recaps to open the curtain on my development as a writer. Substack is a community of writers, so maybe folks can find inspiration here. Perhaps you’ll find a book that you need to pick up to move your craft in the way you want it. Creative Calabash also is a community of people who care about me, so some folks may appreciate this gaze into my creative thoughts. It may help us make connections or collaborations down the road.

Here I share my official bibliography notes that I submitted to the school and add a little personal note to each book for the Calabash. Little summaries of 20 books makes this a long post but I hope it can provide something new or provocative to you.

I begin and end the list with special shout outs to books that moved my creativity in specific ways.

Coetzee, J. M. Boyhood : Scenes from Provincial Life. Vintage Digital, 2015.

Boyhood is a memoir written in the third person. What is remarkable about this book is how he leads into important scenes with characterization, and generalization. He doesn’t explicitly describe the narrator getting older; instead Coetzee describes his changing interests. Chapter 17 begins by describing how his former interests and toys no longer interest him and he doesn’t even know why. Cricket is his only passion from before. He finds his parents’ book on sex and then describes his classmates as potentially sexual beings. This book is fearless in its details, while still moving between generalization and scene. The book is fearless in describing what the narrator wants at various stages of life. He doesn’t feel compelled to explain why these desires change. He just describes concretely the desires of boyhood in the various contexts and adventures of Coetzee’s South African childhood.

Something about that third person perspective opened up my writing about my youth in ways that felt intimate and moving. It allowed me to inhabit young “William Ivy Copeland” in ways that felt closed off to me in my previous attempts. I wrote “messy” right after reading this and am excited this semester to explore other moments with this technique. In this little piece I move from the boy who attended family gatherings on Detroit’s east side to the boy who his his head in books and stories back home at the west side.

Alison, Jane. Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative. Catapult, 2019.

This book is a valuable guide for writers looking to explore how narrative structure can relate to the meanings readers can obtain. Alison picks up shapes found in nature and holds them to our attention. These shapes use repetition and syntax to move meaning forward in ways other than “plot.” Writers use these shapes to create textured meanings. Writers also can use these shapes to unfold characterization by giving readers parallel plot points or characterizations or even using parallels of imagery or symbolism. There is great possibility for these books to be misunderstood, viewed as “boring”- to have these aims not apprehended by readers.

This book is a crucial, must read for authors who see themselves as working “non-linearly.” One of the things implied in this book is that it’s ok if not everyone gets or likes your shit. Some people like linear shit and the certainty that an author may provide.

Clark, P Djèlí. Ring Shout. Tordotcom, 2020.

Will I introduce the concept of “spiritual warrior “ in my nonfiction writing? This book has strong horror elements where the Ku Klux are demons and the Klan are white folks caught up in the hatred that the Ku Klux are manipulating.Three Black women, in this novel set in 1920s Georgia attack these demons with sword, gun, and bomb. The demons, and the women are part of a broader scheme to feed on fear. Not everyone could see these demons, in this novel. Now, what are the concepts of spiritual warrior- implicit and explicit that guide my nonfiction writing? What is the warfare? What is the danger? Where are the moments of comradery where we laugh and sweat together, knowing what we are up against?

Yeah, I hold back from my official school writing. I can’t wait to graduate. And keep it crispy a buck fifty.

Collins, Kathleen. Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? Granta Books, 2016.

This book has been very influential to me. For two reasons, I hope that it opens up possibilities in my writing. First, it centers relationships and the different perspectives people have within their relationships. Secondly, many of the stories take place in the 1960s, and they carry the energy of a time in which people thought new possibilities were arising. Some of the stories also deal explicitly with intergenerational differences in such a time of change. Thirdly, I decided to say it, it includes white characters and what they think of race, and what they think of America; not only what they think but how their thoughts affect their actions. Not only does she writes characters that I find so interesting, but the situations they find themselves feel so resonant and real.

I think about living in creative community in Detroit. How do I write that? This collection of stories is dope, conveying the energy of people not only living together, but thinking into and against each other and the times they live in.

Daye, Tyree. A Little Bump in the Earth. Copper Canyon Press, 2024.

This book is a powerful magic at the confluence of the social and the metaphoric. Think Poppa was a rolling stone but with poppas, mommas, cousins, granddaddy, children and other kin folk all together forever and ever in Youngsville, North Carolina. In this place relationships are tenderly conveyed. People shimmer and are transformed. Through remembrance and touch and the act of looking again we are transported to the land where we “never die” and the touch, and the eating, the feeding, the talking and writing takes place among the dead and the living.

I want to consider how to write Detroit, how to write a place where we know each other and mean something to each other, how to tell a story that isn’t just “my story”. And this little bump is where the spirits and old folks and niggaz and tricksters are observed and held with love and dignity.

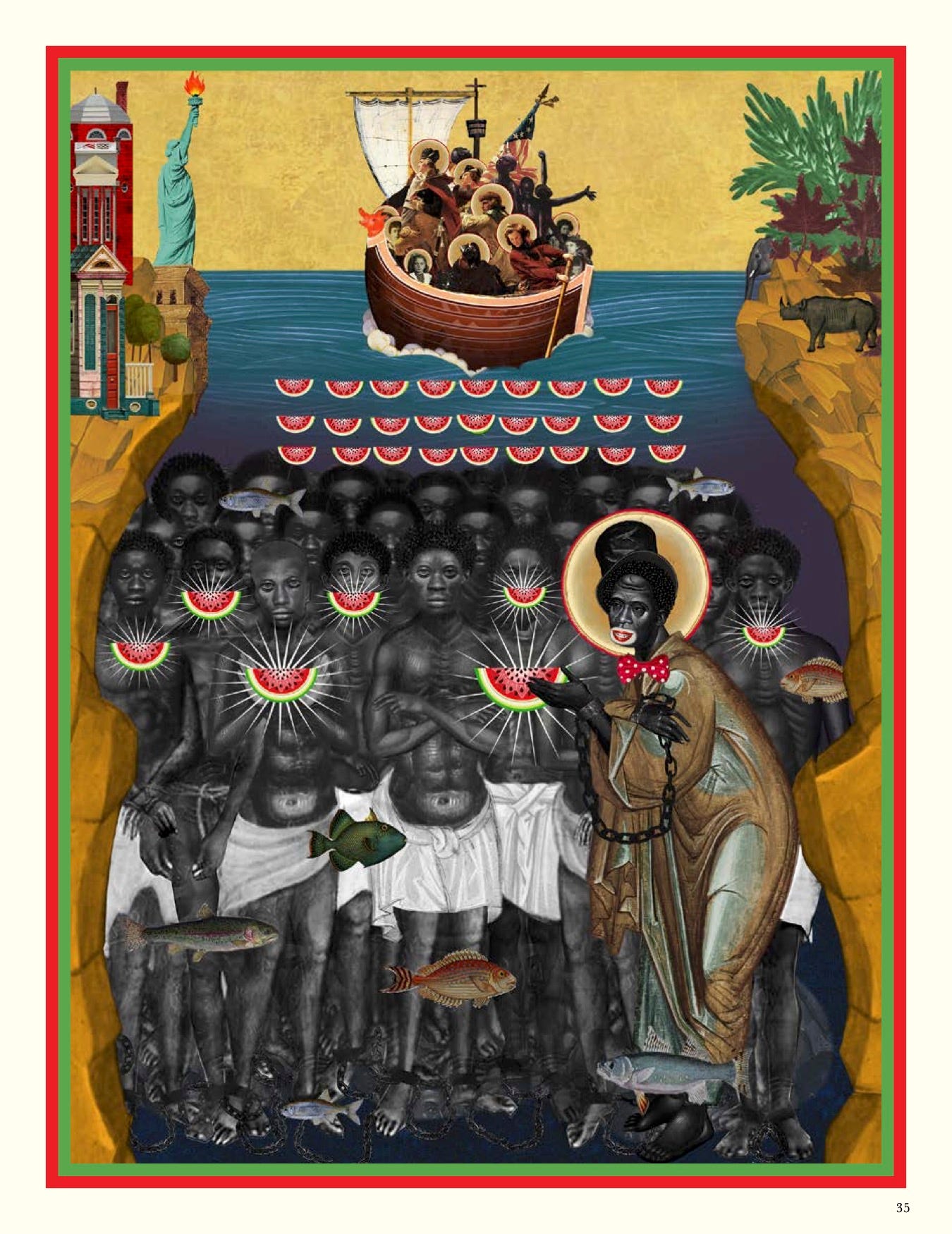

Doox, Mark. The N-Word of God. Fantagraphics, 2024.

Mark Doox has crafted a book which is creation story, allegory, and art book. The N-word of God caused me to jump with surprise and laugh with recognition. A large part of that is the visual art, which I won’t go into much detail about. Doox uses Christian iconography in the Byzantine style and uses Biblical language to make a Bible of the Black experience. He builds the book’s satire with surprising visuals, referential narrative structure, and creative concepts. In order to shine a light on this contradiction, the social state that would deny beings called Black sacredness and dignity while claiming to be religious (Christian) and holy, he must repurpose the syntax and imagery of these hegemonic religions.

This shit is mindblowing visual satire. I can’t yet say how it will affect my writing but I love, love, love this blasphemous, satirical mother fucker.

Dumas, Henry. Echo Tree. Coffee House Press, 21 May 2021.

An astounding range of stories that embody the rhythms of Black culture, folklore, mythology, and life. What strikes me is the leaning into allegory where characters are lightly described, often not given much back story besides the events that are the present focus of the story. Sometimes even place is lightly described “village” “country” “city” “Hell”. Sometimes the specificity is less important than the social relations being described. In these stories, you don’t get individuals mired in personality, you get essences of Black life rubbing up against the contexts America puts us in. “A cheer leaps up from them such as the white men have never heard. A sound of distance and presence, a shaking in the air…”

Dumas is unafraid to speak creatively, yet directly to the spiritual war we live with; because of this, his stories feel, to me, like clarion calls, dizzying and fortifying like courage flying forth from a bottle. Here is a flock of stories that consider deeply what Black life feels like.

Eubanks, W. Ralph . Ever Is a Long Time. Basic Books, 2007.

When Eubanks discovers his parents’ names are on a list of people being investigated by the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission, it sends him on a journey to investigate the Mississippii of his1960s childhood beyond his personal experiences in rural Mount Olive. With well placed transitions, the memoir alternates between three modes: 1) Memories of his childhood, family life and schooling; 2) A travel narrative of Eubanks’s repeated return trips to Mississippi to research the Sovereignty Commission and give context to his childhood; and 3) Exposition and description of news, events, and people of the 1960s Mississippi. Eubanks’s description of his own childhood naivity about race in Mississippi allows him to speak to readers who have a variety of political views on race in America. The reader is invited to learn along with Eubanks. Because his descriptions are specific, factual, and later include personal interviews, any reader no matter how well versed in history of Mississippi of the 1960s will learn.

One of the greatest things about this book to me is that Eubanks poems by saying there were years between when his son asked him “what was Mississippi like” and for him getting the courage to go South and start the research that would become this book. Sometimes our shit just has to marinate.

Febos, Melissa. Body Work : The Radical Power of Personal Narrative. Baker & Taylor, 2022.

This book is something of a writer’s memoir/ craft book. In it, Febos sketches some of the transformations she experienced in writing her books. Memoir is not merely the exposition of past events, it is the revelation and confirmation of who the author used to be. Febos connects who the author is (and what choices they are able to make) with what they are able to write about honestly. Febos also encourages authenticity, which to her is questioning the scripts and conditioning that the author has inherited, often unthinking. Authenticity is also dropping rules of what one can’t say or how one is not supposed to write. Thus, writing is a way to face directly the stories that haunt us.

Febos is no joke. I’d love to apprentice with her. Her shit is silky smooth and full of hard earned reflective wisdom. Definitely someone who has learned how to share her story/stories. She writes like a teacher who has experience pulling words from the mute areas of her students’ hearts.

Gladman, Renee. Prose Architectures. Wave Books, 2017.

Prose is linear and is said to move. This book is a collection of images that is the author’s attempt to capture the energy of writing without writing about writing. They call it “an inner syntax.” It would move me more if the images were attached to writings, if the prose architectures evoked specific texts, paragraphs, or pieces. For me, it's a mysterious calligraphy but I don’t get more from looking at 100 than I do looking at 10. Fred Moten’s “afterword” doesn’t help. He calls the book a “portrait of the bass line,” but it’s a rhythm I don’t (yet) feel.

The introduction, the book, and the afterword helps me to realize that, for me, writing is a process of meaning making and meaning evoking. I think that I am supposed to add my own meaning to these notations and haven’t shifted my perception to do it.

Harjo, Joy. Crazy Brave : A Memoir. W.W. Norton & Company, 2013.

This book will teach me how to write memoir. What I see here: a combination of scene, routine, blurriness, forgetfulness, dreams and visions, poetry. An expression of what moments meant. Harjo places herself in a world where stories have power and where spirits help and hinder. The book is organized as East North West and South, and each of the four directions has a teaching that relates to Harjo’s life experiences. Details aren’t given, ritual is honored but there are moments when she needed healers’ interventions.

I’ll have to pick this one back up when the time is right to further explore memoir. I applied to the American Indian Institute of the Arts MFA but chose not to go there as I was unsure how I’d be supported, how I’d experience community there as an Afrikan. This OG’s book that tells a personal story as a story of memory and culture reminded me of why I applied and why indigenous writing gives me so much.

Indigenous 100s Collective. Say, Listen. NP: Press, 2023.

This book feels like an informal conversation among friends. Each entry is in 100 word segments that offer a completed reflection. The book was written by a collective of 6 authors. They take turns and write their 100’s in conversation with each other. As such the book embodies collaboration, which is rare in the realm of literature.

I love writing 100s. It’s a poetic form that hits all the right buttons. A series of 100s is a sketch and a fractal. A collection of small images which reveal themselves to the reader when viewed up close and at a distance. More than a mere fragment, the 100 can be used to reflect the vividness, the sharpness and partial nature of a memory (like mines) that doesn’t pretend to be linear, detailed and reconstructed into a whole.

Kang, Han. The Vegetarian. Crown/Archetype, 2016.

This novel explores the psychology of the individual and the group. On the surface the brutal novel appears to be a story of a woman’s decline but more and more is revealed and the story tells of an ecosystem steeped in violence that tells itself it is normal. What is worth study is how the atmosphere is created around the character’s actions. How setting, environment and tone are used. How the author uses precise word choice to hint at character’s intentions and point the reader’s sympathies and disgusts in specific directions.

Laymon, Kiese. Heavy. Simon and Schuster, 2018.

What catches my attention is how this memoir does not shy away from political vision, but it lays out its politics with tenderness and vulnerability. Grandmama was born “a poor black girl in Scott County, Mississippi” and in one paragraph of a tender conversation between her and Laymon we get a deep emotional tenor of decades of racial discrimination and sexual violence not as an issue to be inspired or angered by but as survived and embodied in her flesh and in her relationshi with her grandson. He reacts to “sexual violence, heteropatriarchy, mass incarceration, mass evictions, parental abuse” by considering what is needed to give Black children experiences of love, liberation, and imagination. Given that we have read an entire book on his Southern childhood, we have seen these terms come to life so that they are not mere terminology, no one’s jargon, but an authentic invitation to imagine a country that could produce other pathways of living that we could call liberatory and true.

The writing is so full of emotional confrontation, a man confronting his own emotions and the emotions, thoughts, and behaviors of his younger self. I love this exploration of Black manhood and wonder what a reader’s experience will be reading my book and Kiese’s back to back. He makes me want to step up my craft, my curiosity, my precision and my vulnerability more than anyone else.

Lin, Jami Nakamura . The Night Parade. HarperCollins, 2023.

Each chapter of this “speculative memoir “ features a beast from Japanese or Okinawan folklore or legend. The book is at the same time a cultural reflection on what it means to be a child of diaspora looking to reconnect to cultural lineages and a very personal exposition on what experiences of mental illness, grieving and parenting mean to the author. Lin flows between identifying with the monsters and identifying with the villagers who navigate the threat of the assorted beasts. The book exudes a fluidity throughout.

What does it mean to want to reconnect? What does it mean to try to reconnect? I’d love to see more cross-cultural communication about what is lost in assimilation and education and how we, who fly decolonization as a banner or a prayer flag, are trying to reconnect with our parents and the Ancestors who precede them.

Nelson, Maggie. Bluets. Wave Books, 2019.

My partner Bridget read some Bluets and said “this is the whitest book I have ever read.” “It is the business of the eye to make colored forms out of what is essentially shimmering.” Maggie Nelson, being a professional writer, made a colorful form from combining her sorrow at a break up with philosophical musings.The book begins with a hypothetical “Suppose I were to begin by saying...” It’s an intellectual book, full of pondering, settings and scenes are far and few in between. It intellectualizes emotions. Settings are used with little detail to establish the narrator as a high class art consumer: “the Chelsea Hotel” “traveled to the Tate in London to see the blue paintings.” Nelson writes about depression and drug use. The “blue” could thus suggest a muted emotional experience. Writing that “kills the time” may be enjoyable for some readers.

Funny how this book was talked about in the nonfiction world and put on a pedestal by some classmates around me. It is, to me also, one of the whitest books, a product of this moment in an anxious well-educated America that some will relate to and others won’t.

Voigt, Ellen Bryant. The Art of Syntax : Rhythm of Thought, Rhythm of Song. Graywolf Press, 2009.

This is an essential craft book for poets that asks, “How do sentences create the music of our language?” It helps us to move beyond the discursive, that which can be summarized. The Syntax helps us to reach the figurative, the affective, the impressions that writing can create. Variations in meter and grammar are the author’s significant tools which combine to amplify the poem’s effects. We can reinforce the poem’s themes. We can paint subtle pictures with a symphony of structured sound.

If you want to investigate how the sounds of this English thing help make meaning, these lessons may be a useful guide. Be prepared to study and focus. The book is dense.

Wilk, Elvia. Death by Landscape. New York, Catapult, 2022.

This book moves! It begins as a book of criticism, exploring relationships of fiction to the ecologies that surround us and those we imagine. It becomes a meditation on writing and story telling and then shifts further into a personal interrogation of what writing means to the author. The first two thirds is really an exploration of ideas that stem from the author’s engagement with books and stories, and thinkers who philosophize about the author’s interests. She skillfully summarizes and draws questions from the texts she considers, then links them within the essays as well as lightly connects essays one to the next to pen a broader consideration. Does the book feel weird? Does it feel like an ecosystem? Or are these just the topics Wilk considers? I think it’s the latter as the book is an author thinking, reflecting and considering in the context of her life as an American in the Anthropocene. I don’t think I’m left with a sense of “the weirdness of the world” instead I enjoy Wilk’s reflection on how Americans of these chaotic times struggle with and towards weirdness and the role fiction can play in our struggle.

I loved playing with this book in light of my own resonance with surrealism (coming from my exposure to Detroit poet playwright Ron Allen). I started a piece on weirdness and surrealism and put it to the back burner. Surrealism, as we relate to it in the Edgelands, carries with it a critique of the mediocrity of normality. So much more than mere weirdness, I’d say. It is a motion towards an extremity of reality. A call towards a vitality that exceeds “realism” and what is considered “realistic.” I became too shy to bring the piece back out and finish it.

Zeineddine, Ghassan. Dearborn. Tin House Books, 2023.

This collection of short stories features Dearborn as a place that has great meaning to its characters. The book mentions street names and shops and above all, carries complicated feelings of belonging for its Arab American and Arab immigrant characters.The book also includes compelling portraits of relationships between generations and how younger adults make relationships with elders whether parents, neighbors, or employees.

So much fun! I loved this little peek into Dearborn and Hamtramck. And the stories were so imaginative, perhaps surreal in how they uplifted relationship patterns that felt real but combined it with plot and characterization that felt extreme, arresting, eye catching (or eye-popping). It’s so great to read real local flavor in short fiction. One day…. One day…. One day I’ll put a fiction hat on.

I wanted to save the book this semester that hit my in the heart the hardest for last. To thank those who made it to the end of this post. This is the book that I didn’t know I needed to read. It inspired at least 3 reflective essays; there will be more nonfiction to come (I’m trying to finish some threads I picked up previously, aka Collapse, a meditation on gentrification and Detroit in the age of planetary upheaval.) Here’s the first.

Dawes, Kwame. Natural Mysticism. Peepal Tree Press, 1999.

In Natural Mysticism, the Jamaican poet laureate investigates how reggae gave shape to his aesthetics and cultural style, not just as a fan of the music, but as a writer, a thinker, and a Jamaican cultural worker. Kwame Dawes’s book combines memoir with lyrical, literary, and cultural analysis to show how reggae’s postcolonial aesthetic made a generational impact.

He describes how, though he loved books as a child, reggae music created a magnetism that swept him and his folk into new creative (and social) possibilities. Dawes points out 4 aspects of the reggae aesthetic. First its ideology, which includes mythology, cosmology and historical concerns. Second, are the ways that it uses language politically and formally. Third, the particular way that reggae music addresses its themes. Finally, the form, the internal structures of the music and the cultural creations such as dance that bloomed around it. This book is very thought provoking for me to investigate how hip hop has influenced by aesthetics and how I see myself as artist.

If you read this far, thank you! Let me know if you have questions about MFA study, writing journey or if any of these books or authors are interesting to you!

(My cardiologist says I have heart arrhythmia, blah blah blah, risk of this and risk of that; increase this medicine by 50%, blah blah blah.I still am a Child of God through it all cultivating an experience beyond the Western materialism that surrounds us. Ase!)